Learn to Transpose, Step by Step

Transposing... what does that mean?

Just imagine: You play the clarinet and you would like to play some

music with the girl next door who is playing the flute. You take her book,

and with the two of you together you start to play the first melody on

page one. How long do you think your performance will last?

I guess: not longer than a second or three...

It sounds HORRIBLE ! ! !

Why?

If a flute player sees the note C and plays it, you will indeed hear the

note C, for flute is a non-transposing instrument.

But if a B-flat clarinet player sees the note C and plays it, you actually

don't hear a real C, but a B-flat.

The pitch of the note sounds a whole note lower than notated.

As long as the clarinet player plays alone, or together with other B-flat

instruments, it doesn't matter, but when a clarinet player wants to

play along with a non transposing instrument, like a flute, a piano,

a keyboard, a violin, or other C-instruments, than he should copy down

his music on a separate sheet of paper and transpose it into another key,

for only then it will fit together, only then will it sound well together with

the other instruments.

Transposing is to summarize in three steps:

1 - write the right key signature.

2 - copy down the notes in the right pitch.

3 - fill in the accidentals.

How to do this exactly we will learn below.

T I P !

If you scroll down and glimpse at the pictures and the text,

it will seem to be a very long and complicated story.

So: Don't do that!

Take the time to read each block of this page and copy down

the example of the notes.

If you do, you will find out it really is not difficult.

How to find out whether your instrument is a transposing instrument or not.

Play a C on your instrument and compare the sound of it with a C played on a piano. (or an organ or keyboard) If the C you played on your instrument sounds in the same pitch as the C on the piano, you don't have a transposing instrument.

If you discover that the note which was notated as a C for your instrument happens to be a B-flat on the piano, then you know your instrument is a B-flat instrument.

Is the C you played on your instrument an A on the piano?

Then you have an A-instrument. Etc.

You still can't find out? Ask your music teacher, or another person who plays the same instrument you do.

You now know to which key you have to transpose? Then you may go on with the next block of this page:

Click here and scroll down

B-flat instrument (Si bemol)

(like a B-flat Clarinet, a Trumpet or a Tenor saxophone)

E-flat instrument (Mi bemol)

(like an Alto Saxophone or a Bariton Saxophone)

F instrument (Fa)

(like an F Horn or an Alto Oboe)

A instrument (La)

(like an A Clarinet)

How to transpose for E-flat Instruments

Step 1 - Write the right Key Signature

Just imagine we are going to play the next melody together with a violin,

then we will need to change the pitch of our part, in order to play the

same notes the violin does. We need to transpose the violin melody to

make it possible to play it on our E-flat instrument.

So, take a sheet of music paper, a pencil and an eraser, then we can start.

(Click here to print blank staff paper.)

The melody we're going to transpose:

You will notice the flat between the clef and the time signature.

You can't just copy out the flat, for we're going to write in another key, so

we also need different flats or sharps than we had in our original music.

The first question we'll have to ask ourself is:

Which key signature do we need?

In the example above we see one flat, this will become two sharps for an

E-flat-instrument. So write on your sheet of staff paper a G-clef, the two

sharps (f-sharp and c-sharp) and the time signature.

This brings us to the next result:

But how can we know which flats or sharps we need to write in between

the clef and the time signature?

Therefore you look at the table below.

Search on the left column for the sharps or flats as you find them

in the original music, then you will find the key signature you need

on the right for your E-flat instrument.

Table of Key Signatures

for E-flat Instruments

No sharps or flats in the original music?

Write down three sharps: F-sharp C-sharp and G-sharp.

One flat in the original music?

Write down two sharps: F-sharp and C-sharp.

Two flats in the original music?

Write down one sharp: F-sharp.

Three flats in the original music?

In that case your music doesn't need any sharps or flats

Four flats in the original music?

Write down one flat: B-flat.

Five flats in the original music?

Write down two flats: B-flat, E-flat.

Six flats in the original music?

Write down three flats: B-flat, E-flat, A-flat.

Seven flats in the original music?

Write down four flats:

B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, D-flat.

One sharp in the original music?

Write down four sharps

F-sharp, C-sharp, G-sharp, D-sharp.

Two sharps in the original music?

Write down five sharps:

F-sharp, C-sharp, G-sharp, D-sharp, A-sharp.

Three sharps in the original music?

Write down six sharps:

F-sharp, C-sharp, G-sharp, D-sharp, A-sharp, E-sharp.

Four sharps in the original music?

Write down seven sharps:

F-sharp, C-sharp, G-sharp, D-sharp, A-sharp, E-sharp, B-sharp.

Feel free to use the table above as often you want, but the next rule could be helpful too:

Original music 0 accidentals - E-flat-instrument 3 sharps

Original music 1 flat - E-flat-instrument 2 sharps

Original music 2 flats - E-flat-instrument 1 sharp

In all other occasions the E-flat-instrument always gets 3 flats LESS, and 3 sharps MORE than the original music in C.

(You can check this with the table above.)

Step 2 - Copy down the notes in the right pitch.

Take a look at your paper, what do we have?

Just the clef, the key signature and the time signature.

So now it's time for the second step: we're going to fill in the notes.

If an E-flat instrument plays a C, we don't REALLY hear a C, but an E-flat,

as you could read above, for that was why we call it an E-flat instrument,

remember?

When we think like that we realise that when we play a C and hear an

E-flat, we know our instrument is playing a note (two semi-tones)

lower than the written music.

What would happen if we would write two notes below the C; an A, could

that perhaps sound like a C?

Yes!

So that's what we are going to do.

Write out all the notes of our example melody, but in another pitch: exactly

two notes (three semi-tones) below the printed music.

A very important thing to remember is:

Be careful only to copy the notes!

Never and never the accidentals in between the notes ! ! !

Perhaps you think: But this way it doesn't correspond with the original

music!

No, that's right, but we will straighten that out later on this page.

First things first: what you do now is to rewrite the music two notes lower

than the the music on your sheet. The D becomes a B, the E becomes a

C-sharp (you don't need to write that sharp, the key-signature-sharps

take care for that), the F becomes a D, and so we go on, move all

music notes two notes down:

And here you can see how it looks like now.

Step 3 - Fill in the Accidentals

Look at the music above. You will see it immediately: the third measure

isn't ready yet. In the original music we see a natural B and a C sharp, how are

we going to transpose that in our written music?

Just copy it out? Writing a natural and a sharp too?

No way!

Besides, it wouldn't make sense. just take a look: we can't write a natural

in front of a G can we? The G in our music didn't have a sharp or a flat, so

what would a natural be able to do? The G we wrote down is natural already!

When we transpose we should forget the words: 'Sharp', 'Flat' and

'Natural'. Let's take a look, to see what they exactly DO with the notes...

A sharp RAISES the pitch of the note by a semitone, so from now on we

will not talk about 'sharp' anymore, we will call it a 'raise-up-sign'.

A flat LOWERS the pitch of the note by a semitone, so from now on we

will not call this 'flat' anymore, but a 'lower-down-sign'.

A natural in front of an F-sharp, LOWERS DOWN the F-sharp to an F,

so in this case the natural is a 'lower-down-sign', just like the flat.

But a natural in front of a B-flat RAISES UP the B-flat to a B, in this

case the natural is what we call a 'raise-up-sign'.

Let's take a look again at our example:

In the third measure you will notice the natural in front of the B-flat.

What does that natural do?

It tells us the B-flat should go back to its natural pitch, the B.

It RAISES UP the pitch, from B-flat to B, so this is a 'raise-up-sign'.

This means we should add a raise-up-sign in our written music too,

in front of the G.

What is a raise-up-sign in front of a G?

Right! A sharp!

In front of the C in our printed music, we see a sharp, this again is

a raise-up-sign, so the A in the written music should get a raise-up-sign

too.

A raise-up-sign for a A is a sharp.

This brings us to the next result:

Now you have finished, the transposed music is ready to play.

You can transpose all your music like this.

What if you dont't want to transpose from C to E-flat,

but the other way around: from E-flat to C?

In the transposing course above you learned to transpose C-music into E-flat-music.

Ofcourse it is possible to transpose it the other way around as wel: from E-flat-music into C-music.

In that case you just do the course the other way around.

In the course above you see two kinds of note examples. The black printed music is the C-music. The blue hand written music is the E-flat-music.

When you want it the other way around, consider the blue hand written music as your starting point and change it into the black printed version.

This means that you have to copy down the music two notes HIGHER, instead of two notes lower, and the table has to be used the other way around too: the blue hand written examples are like the music you already have, change this into the black printed notes.

So: 2 sharps then become 1 flat. 2 flats become 5 flats. Etc.

Tenor Saxophone?

We still have one little problem to solve:

We transposed flute or violin music for an E-flat instrument like an

E-flat clarinet. But imagine we don't play the clarinet, but the alto

saxophone. This also is an E-flat instrument isn't it?, so what happens

when we transpose flute-music the way we learned above?

You will understand that the alto saxophone is a bigger instrument, which

sounds much lower than a flute or a violin does.

So, when you want to play the same music on your alto saxophone,

you should AFTER having transposed the music like we did above, copy

down the music once again: one octave higher, to make the music sound

exactly in the same pitch as the flute or the violin did.

However, this often will be way to high for an alto saxophone.

What to do?

Try to play it one octave lower, for an alto saxophone just isn't meant to

play in exactly the same pitch as a flute does.

If this doesn't sound well with the other instruments, you better look for

different music, which fits better for your instrument.

Good luck transposing your music!

Margriet Verbeek

|

Margriet Verbeek

Popular arrangements

for 2 recorders (or flutes) and guitar

Free Folk Songs, Christmas Carols and Light Classical Music.

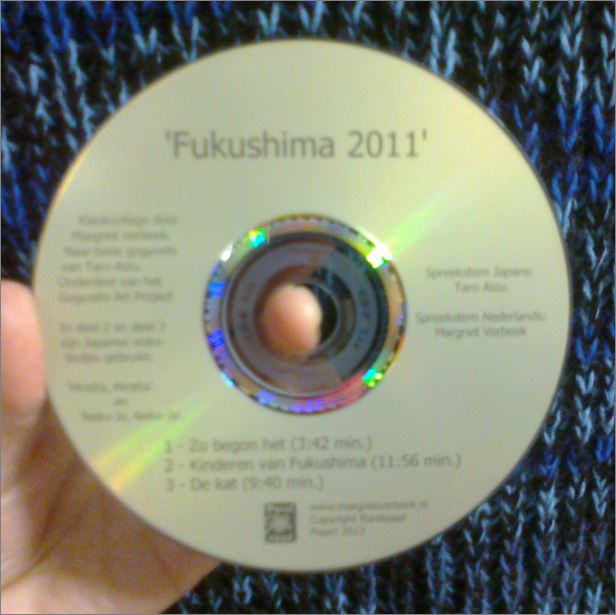

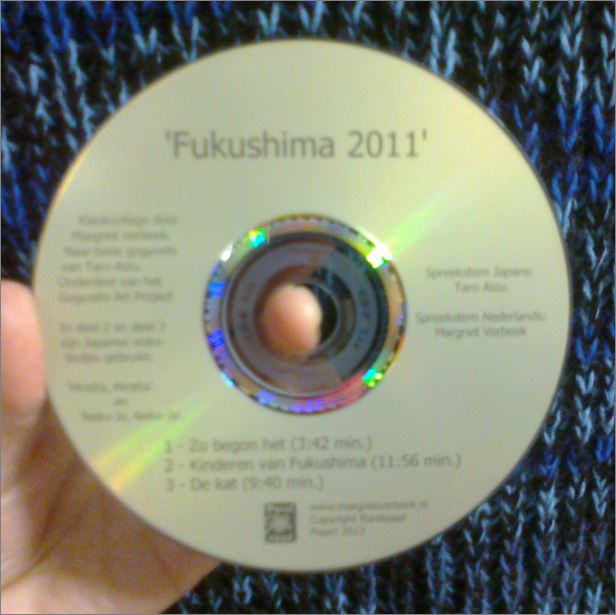

Sound Collage - 2013

This 25 minutes sound collage is part of the Gogyoshi Art Project International,

inspired by Taro Aizu's poems which he

wrote about the nuclear disaster in his hometown Fukushima in 2011.

This 25 minutes sound collage is part of the Gogyoshi Art Project International,

inspired by Taro Aizu's poems which he

wrote about the nuclear disaster in his hometown Fukushima in 2011.

In 2012 was the celebration on the 500th anniversary of the Belgium composer Clemens Non Papa.

50 Dutch and Belgium composers composed for this occasion new versions of his 150 Souterliedekens (psalms) for choir.

November 2011.

Concert in Schiedam to celebrate GeNeCo's centennial (Dutch Composers Association).

May 15, 2010.

CD-presentation in Wilhelminaoord.

Eddy vd Maarel piano,

Margriet Verbeek guitar.

Explaining and performing a Graphic Score with a group of musicians plus the audience, during the European Mensan Annual Gathering in Utrecht, 2009.

The Dutch Association for Mandolin Orchestras celebrated her 60th anniversary in October 2007, by giving a concert in Gorinchem. Their Youth Orchestra performed The Smoking Chimney under the direction of Benny Ludemann. The Dutch Association for Mandolin Orchestras celebrated her 60th anniversary in October 2007, by giving a concert in Gorinchem. Their Youth Orchestra performed The Smoking Chimney under the direction of Benny Ludemann.

Mandolin-ensemble The Strings, at the first performance from l'Artibonite in Bamberg - 2006"

November 2005.

November 2005.

11 members of three brass bands in Midden-Delfland performed Festival in 't Woudt, and Green, Green Midden-Delfland, in the presence of the Dutch Queen Beatrix, directed by Pasha Ashari.

The first price, at the Eight International Competition for Composers in Corfu-Greece (2005), went to the composition

Fleur for solo guitar, by Margriet Verbeek.

|

The Dutch Association for Mandolin Orchestras celebrated her 60th anniversary in October 2007, by giving a concert in Gorinchem. Their Youth Orchestra performed

The Dutch Association for Mandolin Orchestras celebrated her 60th anniversary in October 2007, by giving a concert in Gorinchem. Their Youth Orchestra performed

November 2005.

November 2005.